|

Most operational duties performed by Finance personnel take place after a multitude of government-wide processes that involve several other departments. For example, accounts payable checks are processed by Finance after goods/services are ordered and received, and once their corresponding invoices are approved and submitted by other departments.

Government-wide business processes (such as cash receipts/billing, disbursements/purchasing, payroll and grants) can be difficult to manage because many employees in various departments are involved. In this post we describe one method governments can use to monitor the effectiveness of key internal controls, and we provide templates you can tailor to your government’s circumstances.

The Problem

Major business processes are important to all entities’ success, but they are usually not managed comprehensively. Most of the time, no one person understands the entire process from the beginning in the various operating departments to the end in the Finance Department. There are often few (or no) statistics gathered and monitored to allow the government to understand whether the processes are working well and whether operations are improving or deteriorating.

Major business processes are important to all entities’ success, but they are usually not managed comprehensively. Most of the time, no one person understands the entire process from the beginning in the various operating departments to the end in the Finance Department. There are often few (or no) statistics gathered and monitored to allow the government to understand whether the processes are working well and whether operations are improving or deteriorating.

All complex processes need a feedback mechanism to allow managers to understand how well a process is working and to know when and how to improve it when things go awry. It has been said that –

A process is never static—it is either improving or deteriorating.

Since circumstances are always changing (e.g., new laws, accounting standards, policies, technology, stakeholder expectations, etc.), if you are not currently improving a process, its effectiveness is currently deteriorating.

COSO, the most commonly usedframework for establishing and evaluating internal controls, identifies monitoring as one of the five critical components of internal control.

It states:

Unmonitored controls tend to deteriorate over time. Monitoring, as defined in the COSO Framework, is implemented to help ensure “that internal control continues to operate effectively.” When monitoring is designed and implemented appropriately, organizations benefit because they are more likely to:

Over time effective monitoring can lead to organizational efficiencies and reduced costs associated with public reporting on internal control because problems are identified and addressed in a proactive, rather than reactive, manner.

COSO’s Monitoring Guidance builds on two fundamental principles originally established in COSO’s 2006 Guidance:

What’s the Solution?

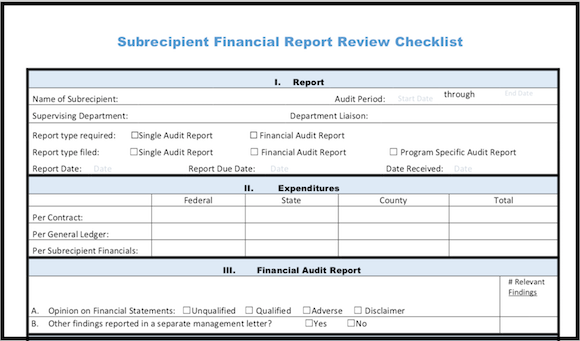

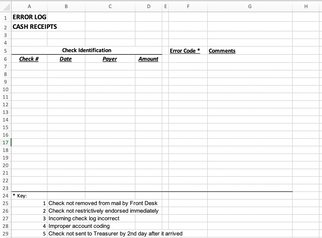

One simple method for a government to monitor their key business processes is for Finance Department personnel – who are processing transactions – to maintain a list of problems and errors that come to their attention at the time the transaction is handled. Any transaction that is difficult, overly complex, overly time-consuming, non-compliant with policies and procedures, late, or incorrect is listed in the error log. (Click here to download a sample Error Log for Accounts Payable and for Cash Receipts in Excel format).

Separate error logs should be maintained for each key business process (e.g., accounts payable, cash receipts, payroll, purchasing, budgeting and grants management). These error logs can be used to determine whether the number of errors is increasing or decreasing. It can also be used to identify recurring issues that increase processing time or risk. Each transaction entered in the error log should have just enough information to identify the transaction and an error code to allow sorting of errors by type. For example, errors in the payables/disbursements process may include (a) amounts input into the financial system don’t match invoice, (b) improper account coding, and (c) department slow to approve invoice for payment.

The error logs should be summarized quarterly and examined by Finance management for trends.

See the two error log templates – one for the accounts payable process and one for cash receipts:

These templates can be tailored to your government’s needs and can be expanded to cover other business processes.

If you have more questions related to the effectiveness of internal controls and/or using error logs, feel free to reach out to Kevin directly:

Kevin Harper, CPA [email protected] (510) 593-503

If you'd like to get more free tips, as well as downloadable tools and templates for your agency, please join our mailing list here!

(We’ll send you a monthly curated selection of our blog posts. You can unsubscribe at any time.) |

The Government Finance and Accounting BlogYour source for government finance insights, resources, and tools.

SEARCH BLOG:

Meet the AuthorKevin W. Harper is a certified public accountant in California. He has decades of audit and consulting experience, entirely in service to local governments. He is committed to helping government entities improve their internal operations and controls. List of free Tools & Resources

Click here to see our full list of resources (templates, checklists, Excel tools & more) – free for your agency to use. Blog Categories

All

Need a Consultation?Stay in Touch! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed